Six or seven years ago my husband and I attended the

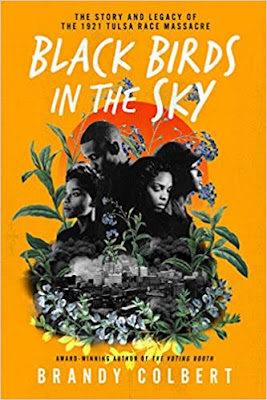

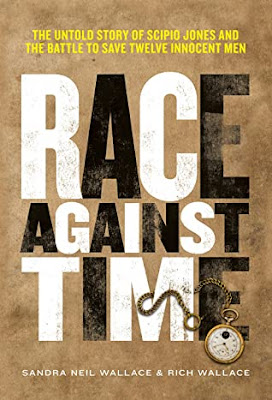

Search for Meaning book conference put on by Seattle University. Each author's offering had something to do with equity or ways for the reader to further understand and appreciate their neighbors worldwide. At this conference my husband and I both attended the workshop conducted by Suki Kim, a journalist who had recently published a book,

Without You, There Is No Us: My Time with the Sons of North Korea's Elite. After her session we purchased this book and stood in line to get Kim's signature. At the time I had the best of intentions to start reading as soon as I got home. Well, six years later I finally got around to it, in part because Helen at

Helen's Book Blog announced she would be reading the book for Nonfiction November and I approached her about doing a read-along. We decided to read it together, five chapters at a time, using our Goodreads message in-boxes for our discussion. It worked super well and I enjoyed the read-along and discussion very much.

Suki Kim, a Korean-American, was born in South Korea and had relatives who were trapped in what became North Korea after the Korean conflict truce divided the two at the 38th parallel. She wanted to know more about North Korea but would only get a sanitized view of the country when she visited it a few times under heavily scrutinized trips. She wanted to learn more about what it was like to live in the most closed-off country in the world so she applied to go teach at a college, Pyongyang University for Science and Technology (PUST), supported by a church. In order for her to be accepted for this volunteer position she had to pretend to be a missionary herself, someone doing this work with an eternal goal in mind. So for six months she lived and worked among the 240 males students, all sons of North Korea's elite. What she discovered about these boys and the country in general was both eye-opening and disheartening.

After reading the first five chapters of the book both Helen and I seemed hopeful that the Kim's experience with the Korean boys would provide a breakthrough for them. Helen said, "I feel like we are on the cusp of students taking chances, opening

up a bit, etc. but it makes me nervous for them, which is the sign of a

good book. I feel invested in what happens." She was right to feel nervous for them because everything anyone did was scrutinized. There were 'minders' everywhere and it was assumed that they were spying on every interaction the boys had with their teachers. Kim and the other teachers had to be very careful what they said. Who knows what kind of punishment the boys would receive if they were caught in some illegal act or thought?

I was struck by how childlike the boys were. Imagine what American college students are like, then think of those same boys as ten-year-olds. The North Korean boys were so naive and child-like. They were more like the the ten-year-olds than the American college students. "For example," I said in my discussion with Helen, "the birthday party where they sang friendship songs for

several hours and teased the boy who has never even been near a girl yet

he thinks himself a Romeo." Later in the book, Suki Kim refers to how much she loves the boys, which struck us as really odd since we are both secondary teachers and we will talk about liking our students but never use the word 'love' about them. My sisters, both elementary teachers, do talk about loving their students. Helen and I decided that this is more proof of how childlike these boys were.

Helen starts the discussion on our next section with the topic of lying. "And the lying is fascinating. It would breed such distrust on the part

of the author/teachers, but to the students, it seems accepted and

something they all do, perhaps to save face?" Lying was so common Kim wondered if the students even knew it was wrong. How could they? They lived in a country where the Great Leader, Kim Jong-il supposedly was the foremost expert on every subject? He also has hit the most hole-in-ones in a single golf game, and knows all there is to know about growing apples. The regime has so locked down the country the boys have no way of checking to see if 'facts' are really true or not. Here they are attending a Science and Technology school without even the most basic Internet available to them.

Our American brains find it hard to imagine someone living under such a repressive regime not pining for freedom inwardly. But after reading the next section we wondered if the indoctrination of the people was complete, if by some miracle North Korea opened up, would these people be able to shake it off? I laughed at first,

about the example Kim used when she described kids singing the beautiful song which devolved into: "burning

hatred in our hearts", such brutal words coming out of angelic mouths"

(150). How can that type of repression be overcome? How could

these N. Korean boys ever escape from the clutches of this regime since

their whole life has been about worshiping the dictator?

Speaking of singing, there was a lot of singing done by the boys and others in the country. Apparently almost all of the songs they sang had something to do with the Great Leader or how wonderful their country was. In fact the book title, "Without You, There is No Us," comes from a patriotic song extolling the virtues of The Great Leader, Kim Jong-il.

As we read on both Helen and I were struck by how tedious existence in North Korea was for the both the students and the teachers. There was little to do outside of studying (students) and lesson-planning (teachers.) Kim knew that her email was being monitored so dared not write messages home that would be seen and viewed negatively. Field trips to cultural sites always seemed creepy and staged. For example one museum held items that were given to the Great Leader by other world leaders. A guided tour of these items ended abruptly when it was time to go into the next room. The teachers were herded back on to the bus without an explanation. There were never explanations.

The bleakness of the place is astonishing. Kim said, " Being in North Korea is profoundly depressing. The sealed border

was not just at the 38th parallel, but everywhere, in each person's

heart.. I was becoming convinced that the wall between us was impossible

to break down..." And in chapter 27 she gets a sense that the boys are

as fed up and stifled as she is. "Every day is the same. / Every day is

about waiting. / I am fed up."

As the end of Fall semester approaches Kim is approached often by her students, wondering if she will return in the Spring. She never tells them no, she just demurs. Are the liars being lied to? Kim never said she wanted to come back but was she willing to go through another term of loneliness and boredom for more writing material? I doubted it. But it all became a moot point because two days before she was scheduled to go home for Christmas, Kim Jong-il died and the whole country went into a spasm of grief. Suki Kim and all the teachers left without so much as a goodbye to any of their students who were all embroiled in their own pain and grief. It was a sad way to end her tenure in North Korea.

I would have liked an 'Afterward' so we could know what happened after Kim got home. Helen agreed. The book ends when she leaves North Korea. I suppose the Afterward is the book and the reflections she is able to make about her experiences only after she has some distance from them.

If you've never done it before, I recommend nonfiction books for a read-along. I got so much out of my discussions with Helen which allowed me to enjoy the experience more. Thanks, Helen, for joining me on this reading adventure.

-Anne