Pedro Páramo:

"The Perfect Novel You’ve Never Heard Of"(Slate)

About two years ago I read a list of 75 books one should read before they die. Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo was on that list. I had not heard of the book but figured it would be good for me to read more Latin American literature and added Pedro to my TBR list. Since then I've noticed the books on several other must-read lists and noted an upcoming Netflix film adaptation. It was time to get more serious about locating a copy of this classic book.

First I searched the library and found that all of their print versions had a long waiting list. The library had an audiobook available, which I prefer anyway, but on closer inspection I determined the recording was in Spanish. Since that wouldn't work for me I went ahead and used an Audible credit to purchase the English translation audiobook. My next challenge was to find a time to listen to the book with my husband who is better at interpreting magical realism or books with deeper meanings than me. Since Pedro Páramo is short, less than 130 pages and only 4-1/2 hours listening time, we were able to complete the book on a recent car trip. And, boy, was I glad Don listened to it with me.

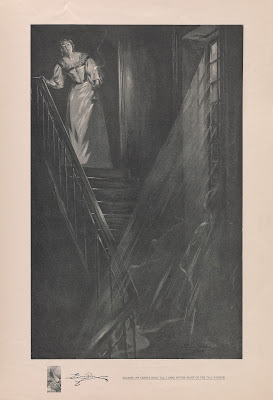

Wikipedia describes Pedro Páramo this way, "This novel showcases the roots of Mexican culture and its beliefs on afterlife through deeply complex characters, spirituality, and a constant transition between realms/dimensions that encompass a nonlinear chronology." Well, that doesn't sound confusing at all (snark)! To add to the mixed-up timelines, the shifting narrators and verb tenses switch back and forth so often that time itself has no meaning. The first/main narrator, Juan Preciado, travels to his mother's hometown, Comala, to confront the father he has never met, Pedro Páramo. When he reaches Comala Juan meets ghost after ghost, though distinguishing the living from the dead is an ongoing and futile effort. The town itself seems to be disintegrating. Through these ghosts Juan learns about the history of this town and of his father. The memories they share do not match up exactly with the memories his mother shared with him before her death. In the end, before he is literally scared to death, he learns the town has become a ghost town because of his father. Everyone died because of Pedro Páramo's cruelty.

At some point during the trip -- midbook, actually -- I looked up information about Pedro Páramo on Shmoop, my favorite go-to spot for literary criticism. The book plays with the question "what is reality anyway?" The reader is never really sure what just happened. "The chorus of ghosties helps keep this sense of dread rolling around in your head not only when you are reading but long afterwards. Isn't that the definition of being haunted?"

A book becomes a classic when it is never done saying what it has to say, making a rereading likely. Pedro Páramo has a lot to say about spirituality and religion, time and memory, madness and suffering, gender differences, and culture and history. The author, Juan Rulfo, was speaking to issues that Mexicans living in the 1950s would understand about the death of rural communities as people were leaving for urban centers and various abuses of the Catholic church. These themes and many others are ones we can still relate to today. Rulfo also played with the names of the characters that perhaps only Spanish speaking readers would immediately understand. Many character names were clearly carefully chosen to reflect personalities, fates, or themes. For example Abundio Martinez, with a name that implies abundance, starves to death.

The version of Pedro Páramo we listened to was translated by Douglas Weatherford, who included an endnote describing his efforts to translate the text the way it was written, which may be a bit more confusing to English readers than other previous translations. Gabriel Garcia Marqués wrote the forward and extolled Rulfo's book and writing in general. Marquez credits Rulfo with really opening up his own career -- and for many other famous Latin American authors -- which we know included the very highly regarded One Hundred Years of Solitude. He read Pedro Páramo over and over. Marquez thinks he could actually recite the book line for line from cover to cover. High praise for a book I had never even heard of.

My rating: 4 stars.